The Past and Future of Civic Finances.

One of my inspirations for starting Notes on Common Ground was Bryan Boyer’s newsletter, Urban Technology at University of Michigan. If your brain’s diet is deficient in sharp ideas about architecture, technology, land, urban planning, and the role of academia, Bryan’s pieces are packed with vitamins.

A recent UT@UM letter focused on The Past and Future of Civic Finances. In it, Bryan makes the case that property tax is one of the few substantial sources of revenue for cities, and points out a number of problems that unfold from that civic finance model. Land transfer tax is capped at a fixed amount, so municipal revenue becomes a function of the property market’s heat. This creates perverse incentives in land use policy that drive up home prices and ripple out to rents. It’s particularly challenging in times of crisis and fiscal uncertainty (as we saw during the COVID-19 pandemic) or slow economic decline (as Detroit experienced in the late 20th century).

The Note explores crowdfunding as an alternative source of capital for civic infrastructure and neighborhood-scale projects. Crowdfunding allows end users (neighborhood residents) to fund what they actually want. It opens up space for unconventional projects, and positions municipal governments as an enabling partner, as opposed to a direct financier (I explored some of the architectural implications in my 2015 book Open Source Architecture).

There are obvious problems with crowdfunding. Should municipalities be passing off financial burden to residents, on top of taxes? No. Should only people who are financially empowered have a say in civic futures? No.

Participatory budgeting is a different model that achieves some of the same goals. Residents can shape capital projects and programs through democratic decision-making. This gets around the problem of direct financial burden, but there is an issue of only getting representation from those who have time, capacity, language skills, and who are comfortable interacting with government institutions. Bryan explores these new models and their challenges with clear eyes.

Future Public Value and Future Public Loss.

The Note is about municipal finances, but really circles around the issue of future public value. This is an idea that I’ve been exploring in other domains — like public procurement of technology — and in parallel with others, like Sam Butler — check out his PlaceFlow application.

Future public value is captured as both financial returns and improved lifeways. Think of a real estate development. The capital investment strategy will define financial returns, and the design strategy will define neighborhood character, walkability, and sustainability.

There are many civic finance tools that shape future public value, like municipal bonds and real estate investment. The most interesting ones, like crowdfunding and participatory budgeting, bring future public value to the resident level. They operate at the human scale (parks and murals and community gardens) and add value (new urban amenities that improve lifeways), as opposed to abstract financial products that benefit institutional investors.

New models for real estate development, for example, might distribute the financial ROI among residents, and bring them into the design process. Frolic is proving this out with community-first real estate projects in Seattle. These kinds of tools are important, and we should work to use them, improve them, and find others! (more on that in my next Note, Part 2 of this one)

But first: there is a flip side of the future public value coin. Consider climate change and public health. This past year has proven that both dramatically shape cities. They are both matters of future public value, but not in the positive sense (maximizing collective gain). They are issues of future public loss, in a negative sense (minimizing collective harm).

In order to effectively think about future public loss, return on investment needs to be reframed as the cost of doing nothing. Neighborhood quality of life needs to be reframed as inequality in the effects of climate and public health crises.

We Have the Wrong Tools!

Conventional investment structures are built to maximize individual returns as a function of an individual risk profile. Unfortunately, these tools still work well. Investors make money during crises. The number of billionaires in America actually increased over the course of the pandemic, and the ultra-rich got ultra-richer. For as long as that’s still true, there won’t be a real incentive to invest in mitigation.

There are a growing number of ‘mission-driven’ investors out there. But there is no effective cross-sectoral capital structure that starts with a collective loss model and strategically invests in a portfolio of products, policies, and infrastructures that will minimize future public loss.

Aha! That should be the public sector’s job, you’re thinking. Yes, in theory, but here again we run into challenges.

Future public loss depends on the investments we make and the choices we take now – but the effects of a mitigation policy aren’t visible for decades. Democratic governments get tilled over with every 4-year election cycle, which dismantles anything like coherent strategic action. Elected officials cycle out before anyone feels the negative effects of inaction. And climate and health are both political hot potatoes! No one ever boosted their poll numbers by making a small but significant behind-the-scenes contribution to a long-term plan for minimizing possible loss.

To make matters worse, climate action and preventative public health require coherent strategic action across traditional sectors (public, private, philanthropic, community) and disciplines (transportation, housing, nutrition, education). That is extraordinarily complex, with many orthogonal (and in some cases conflicting) motivations.

So mitigative action is limited to whatever capital can be scraped together from public budgets (which, as Bryan demonstrated, are not a honey pot) and whatever strategies have broad political appeal and can be achieved in the short-term. That’s not much room to play with.

Preparing for What Already Happened.

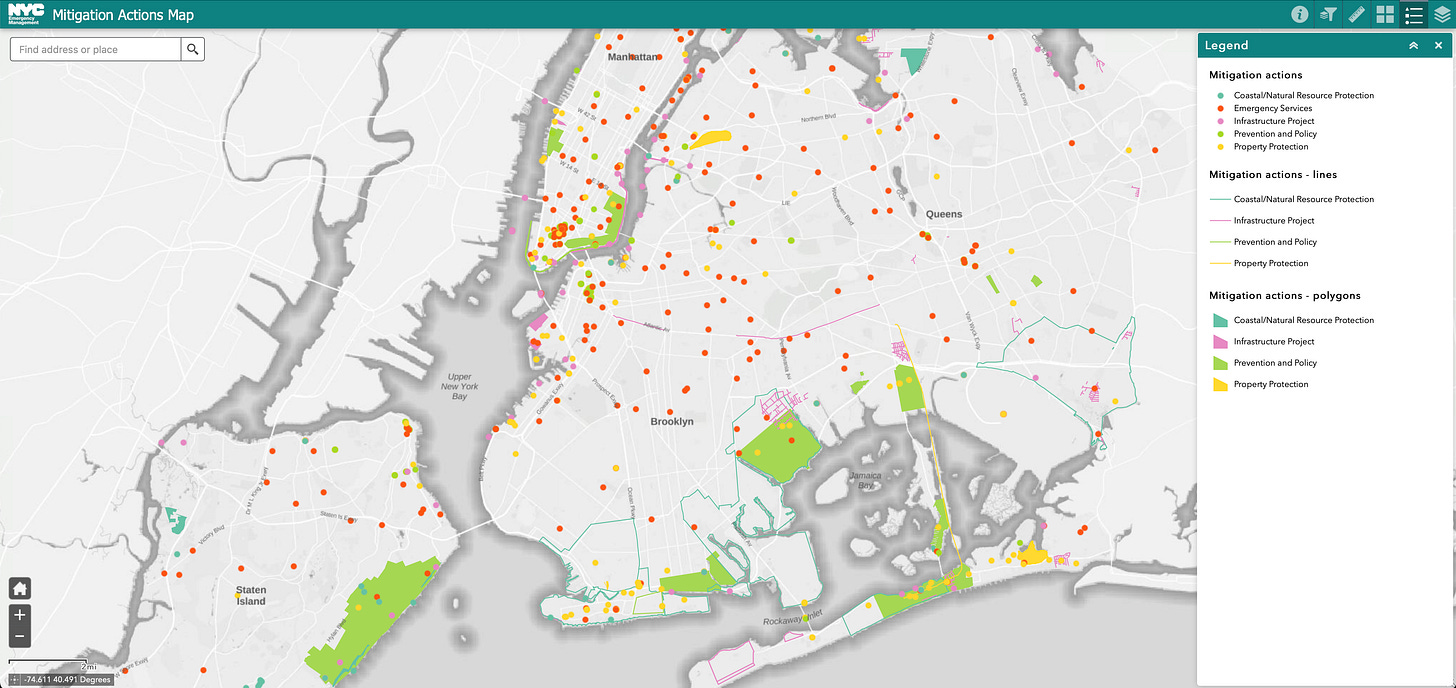

Not much room to play with usually ends up being filled by a marginal response to an immediate crisis that already happened. Take the example of Hurricane Sandy. New York has made some efforts to improve resilience after the storm, on both a political and financial register.

By “codifying New York City’s Climate Resiliency Design Guidelines for all city capital projects, all city-funded buildings and infrastructure — a $90 billion capital portfolio — must now be designed to withstand climate threats.”

Justin Brannan and Karen Imas for the New York Daily News

In other words, New York City is really only preparing for the storm that already happened (not the one that will happen) with money they’re already spending on development projects and infrastructure (as opposed to heavily investing new money in mitigation). This is an oversimplification, but it’s largely true.

The COVID-19 pandemic is another obvious example. In 2016 the National Security Council created a Playbook for Early Response to High-Consequence Emerging Infectious Disease Threats and Biological Incidents. The document was a roadmap for “coordinating a complex U.S. Government response to a high-consequence emerging disease threat anywhere in the world.” The guidebook was completely ignored by the subsequent administration, for political and financial reasons.

Some small, incremental mitigation efforts are happening at the margins, where there is short term political payout and a clear individual financial risk based on (recent) past events. But the reality is that the cost of doing nothing is borne collectively in the long term, while the financial and political gains from doing nothing are reaped individually in the short term.

Investment in resilient infrastructure, ecosystem services, and climate mitigation will prevent the destruction of neighborhoods. Investment in long-term population health and preparing for quick and effective response can shorten or prevent lockdowns. We just don’t have the financial and political tools to make long-term strategic policies and investments in preventing future public loss.

This all sounds cynical and perhaps defeatist — but I don’t mean it that way. It’s important to understand the challenge of future public loss and the shortfalls of our current tools, as a starting point for imagining new ones.

This is Part 1 of a two-part response to “The Past and Future of Civic Finances,” a recent issue of the Urban Technology at University of Michigan newsletter. Part 2 will explore some possible structures for strategic policy and investment, and avenues for aligning loss-mitigation with future public value.