Checkerboards.

I visited the Oregon coast for the first time last week. The landscape is surprising, and staggeringly beautiful. Driving there was the first time I had crossed a significant section of the state on back roads. The route winds through farms and small towns, state parks and protected corridors. Inland farms transition to coastal forest. The landscape is a blur of green. Then a distinctive pattern emerges: sharp, orthogonal lines and bald patches. It’s a tree-top, clear-cut checkerboard.

According to early American homestead laws (including the Donation Land Claim Law of 1850), settlers could buy land for $1.25 - $2.50 an acre — a political effort to promote development. Alternating patches of land along the Oregon and California Railroad were allocated for the program, forming a distinctive checkerboard pattern. Much of the designated land was thick, old-growth pacific forest on steep hillsides — which wasn’t especially useful for farming or living on. But it was great timber. The Oregon Land Fraud Trials of 1904 found a number of industrialists and public officials guilty of illegally colluding to buy the land. The scheme was simple. Round up guys in bars, and have them claim settler status to access squares of the checkerboard. Entrepreneurs gave them some money to buy the land, then transferred it to their timber companies. After the scandal broke, public outcry turned into public interest in land management and forestry, which gave momentum to President Roosevelt’s environmental protection agenda and the creation of the U.S. Forest Service.

I spent the weekend camping near Coos Bay, a historic logging community and key stop on the railroad. It lived its heyday as a town of lumberjacks, small family-run sawmills and lumber shipping. Logging is deep in the history and soul of this state. And the industry is a political-economic-environmental lightning rod. It provides jobs, it irreversibly destroys old forests. It is a source of historic pride, and it is changing dramatically with technological and financial developments. And because the timber industry works such a massive swath of the state, the way it operates has a tremendous impact on the health of Oregon’s land and its population.

My bias is going to be obvious here. I love old growth Pacific coast forest – I moved across the country to be closer to it, and I went camping last weekend to get out into it. The cool, mossy shade of redwoods is majestic. I’m writing now (a week late, sorry, I was camping) with an aching throat, wrapped in the orange light and dirty cottony creep of smoke from wildfires in southern Oregon.

I also acknowledge the history, the pride, and the economic centrality of the timber industry here. Humans need wood, and it has to come from somewhere. It’s important to understand how logging happens and what it means to preserve forest, so that we can do both well.

Logging has changed.

The nostalgic image of lumberjacks in plaid felling trees, and logs drifting down swollen rivers toward family sawmills is no longer a reality. Profound transformations in Oregon’s timber industry have undermined its local identity, contribution to the economy, and above all, its ecological viability.

This started during the 1950s and 60s with a shift to industrialization, enabled by technological advances and legitimized by pseudoscience. Forests became “plantations.”

“During the 1950s, public and private foresters promoted the principle of ‘conversion,’ turning what they considered decadent old-growth forests into fast-growing new stands with shorter harvesting rotations… federal agencies, in turn, aggressively promoted clear-cutting as a scientifically sound practice and increased the use of chemicals as a forest-management tool to control competing brush in newly planted plantations.” (Oregon Encyclopedia)

The next shift, during the 1980s, was financialization. Small companies hadn’t weathered the 1970s recession well, and were ready to sell land. Simultaneously, a clever interpretation of tax code cast forest land as an investment opportunity. Traditional timber companies that cut and mill wood pay a corporate tax of around 35%. But if a pension fund or real estate investment trust owns the land, the fund’s investors pay a capital gains tax of only about 15%.

“Small timber owners, who grow forests that are older and more biologically diverse than what corporate owners manage, have sold off hundreds of thousands of acres. In western Oregon, at least 40% of private forestlands are now owned by investment companies that maximize profits by purchasing large swaths of forestland, cutting trees on a more rapid cycle than decades ago, exporting additional timber overseas instead of using local workers to mill them and then selling the properties after they’ve been logged.” (Oregon Public Broadcasting)

Some timber companies even converted to become real estate investment trusts. The homepage of Hancock Timber Resource Group proudly announces:

“Hancock Timber Resource Group was founded in 1985 by foresters and investment professionals who believed that timberland provided investors with an attractive asset class to further diversify their portfolios.” (HTRG)

As more and more land was sold to investors and worked by timber conglomerates, there was a corresponding push-back. During the 1990s, a strong politics of preservation emerged. A legal fencing match between environmentalists and entrepreneurialist logging companies sparred around the Spotted Owl. The bird is native to Oregon forests, and threatened by intensive logging. When it was granted endangered species status, the owl gained rights of legal representation. On behalf of the Spotted Owl, environmental lawyers won protection for Oregon forests that are home to the owl. The bird is also remarkably cute. It appeared on the cover of TIME Magazine, and became a symbol of forest preservation.

The private logging industry’s lawyers made a deft parry and riposte. Almost all of the private forest land in Oregon had been cut, and a state law required companies to replant trees. If timber companies are planting also, aren’t they really more like farmers? And if crops aren’t taxed in Oregon, why should trees be? Today, the largest private forest holder in the state pays about $4.60 per acre in taxes – 1/100th of the residential property tax rate in the same county, according to an investigation by OPB, The Oregonian and ProPublica.

Shapes and Practices of Preservation

The politics of preservation is personal; I have a stake here; I think we all do. The legal, political, and economic strategy of preservation is an important question – the Spotted Owl proves that. There are tremendously knowledgeable people writing about these kinds of issues, and offering ways to live in response (three that have inspired me most are Terry Tempest Williams, Elizabeth Kolbert and Donna Haraway, good video interviews are linked). The Time Magazine cover summed it up well: it isn’t simple. For my part, I’ve been thinking about the form and the practice of preservation.

I’m certainly not an ecologist, but it’s intuitive that continuous swaths of land – as opposed to alternating checkerboard squares – are important for animals who migrate, hunt, pollinate, drift and graze. In order to create green belts, some are calling for a tidy land swap that turns the old land-fraud-checkerboard into more of a striped pattern.

This would probably do some amount of good (again, I’m not an expert), and there are precedents for this kind of land swap. They prove that the political lift and the economic fight with companies would be staggering (a transaction near Oregon’s Mt. Hood has been in negotiation for decades). It would also mean that squares of old growth could be cut, next to newly protected squares of seedlings on bald hilltops.

Dutch artist duo Bik Van der Pol’s project Eminent Domain is an incisive take on both the politics and the ecology that would unfold from a such a land swap. The exhibition explored the ecological effects of government-facilitated privatization of public land.

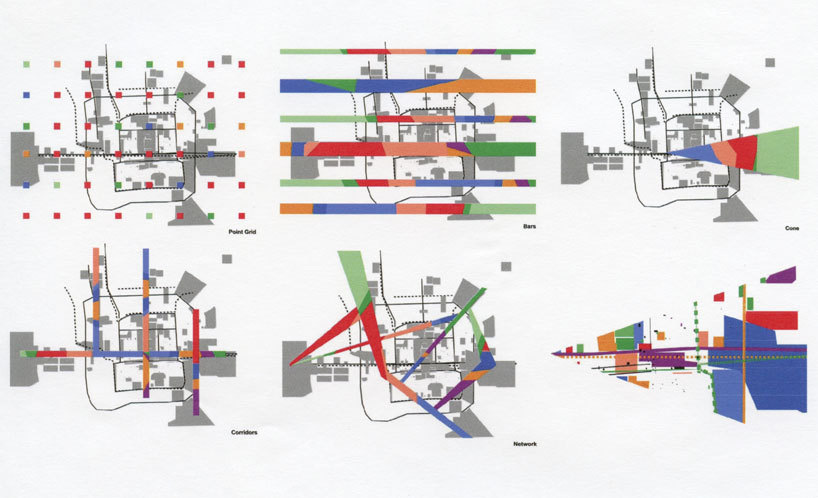

And a land swap wouldn’t change the sharp lines that I saw out my window. In a forest, shapes feel arbitrary. OMA’s Beijing hypothesis resonates – and highlights the absurdity of geometric preservation:

“Different models of preservation can be imagined: a wedge could record, systematically and without aesthetic bias, all the developments that have occurred in an urban system over time; a point grid could act as a form of sampling, a statistical preservation model capturing every urban condition.” (OMA)

Ebbing and Flowing Form

The preservation conversation seems too stark, too focused on absolutes and boundaries. What if the interface between preserved and logged forest is more like a blurry gradient? What if the relationship is a dynamic and discursive one?

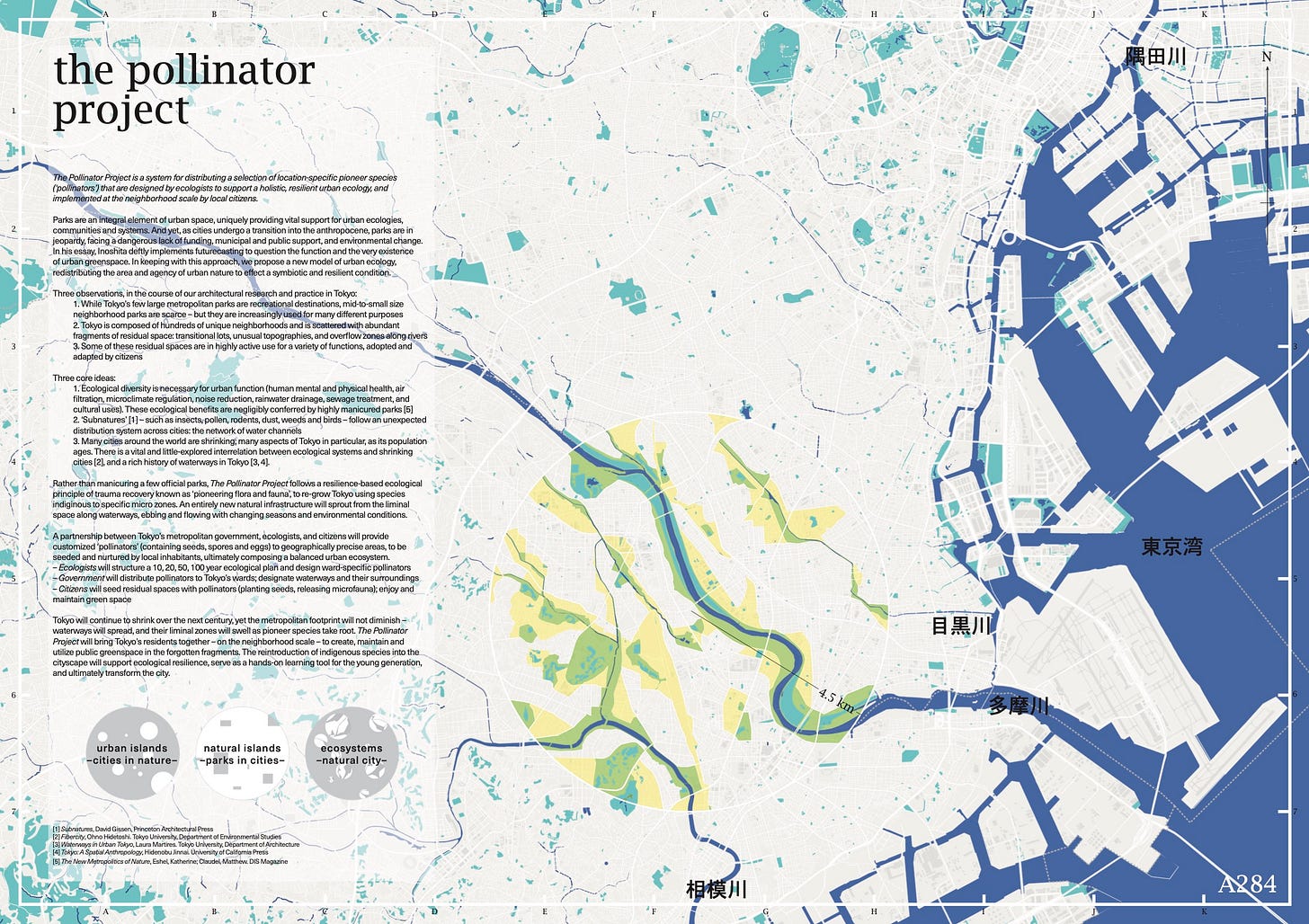

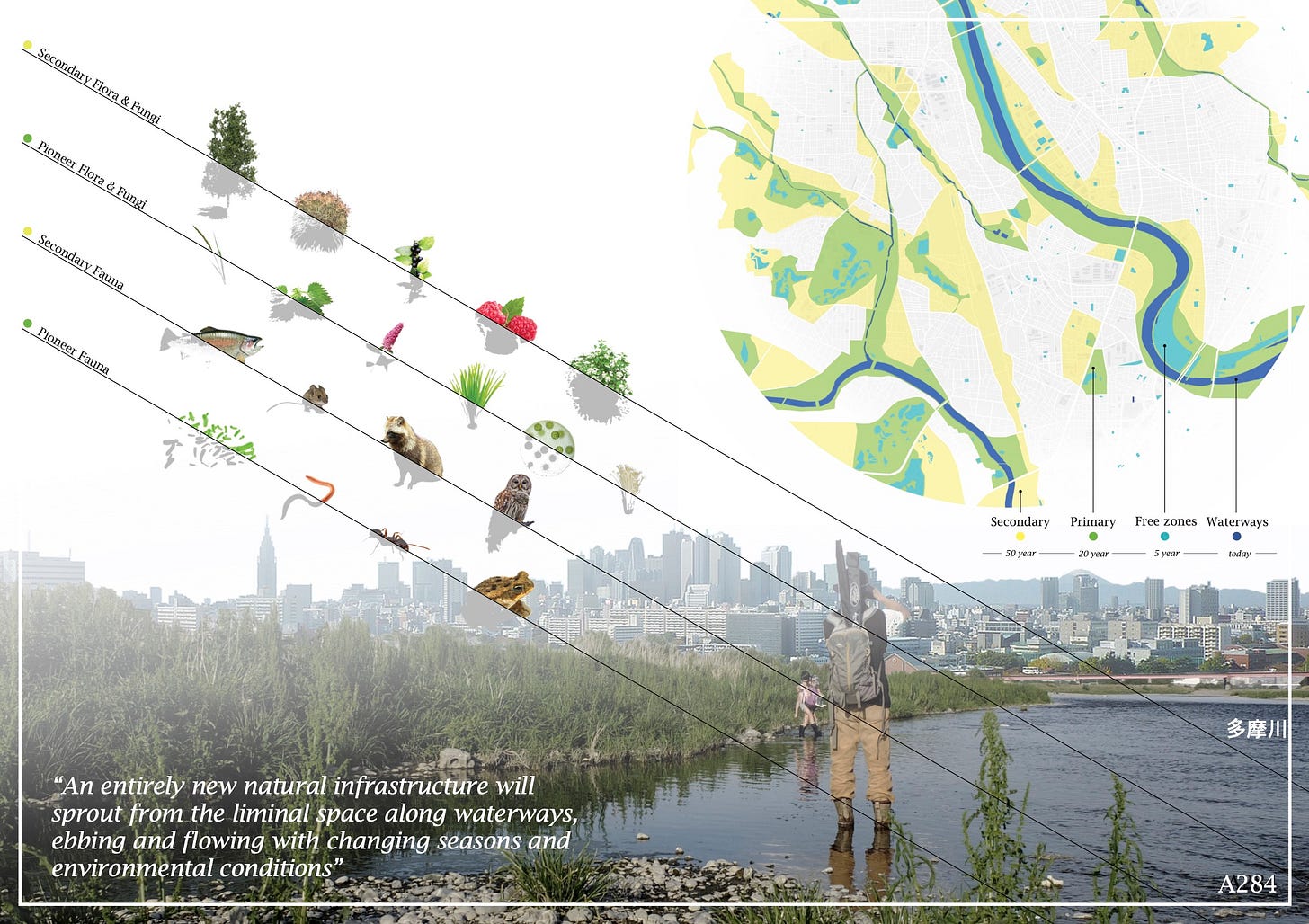

Together with Marie-Eve Brodsky, I imagined this kind of continually unfolding, time-based relationship. The Pollinator Project was our entry to the Japanese Institute of Landscape Architecture’s 2015 urban design competition for Tokyo, called Our Future With/Without Parks 2105. It didn’t win, but the ideas have stuck with me.

“We propose a new model of urban ecology, redistributing the area and agency of urban nature to create a symbiotic and resilient condition… Rather than manicuring a few official parks, the Pollinator Project follows a resilience-based ecological principle of trauma recovery known as ‘pioneering flora and fauna’, to re-grow Tokyo using species indigenous to specific micro zones. An entirely new natural infrastructure will sprout from the liminal space along waterways, ebbing and flowing with changing seasons, urban growth and de-growth, and environmental conditions.”

Both the form and the practice of natural spaces that we imagined for the Pollinator Project could be applied to Oregon’s forests. Rather than a land swap, preserved and logged forest areas could be sensitively interwoven. Land rights wouldn’t be sharp monoliths that are perpetually fixed in time. Forest would neither be carved into parcels, nor tenuously protected by legal affiliation with an endangered species. It would “own” itself, as a legal entity. Squares would be replaced by ribs — along logging roads, perhaps — and the space around them would have a gradient edge that changes over time. The practice of ecology and logging would be an ongoing ebb-flow along the edge. After logging swells out in one area, the forest would be left to push back, regrowing for a century. I imagine this would be more sustainable for the timber industry and for the forest in the long run.

This is idealistic. It would mean unraveling the recent shifts in the timber industry: industrialization, financialization, and absolutist preservation (not to mention closing tax loopholes). It would be a forestry practice based on mutual respect between companies and forests, and a radically different idea of time and of ownership. It would be based on a recognition that old growth has inherent value, and that paths for critters and water and drifting pollen are vital. It would acknowledge the history and pride of the timber industry, and the human need for wood. It would be a mutual kind of relationship that doesn’t permit “increasing” one kind of land or the other. It would be a mutual, persistent, coexistence that breathes in and out over centuries.

Thank you to: Oregon Public Broadcasting, The Oregonian and ProPublica for excellent investigative journalism, Andrew Damitio for ongoing critical engagement with Oregon land politics, Sophie Nitoslawski for brilliant insight into urban ecology, and my wife Kim for inspiring me (and for driving while I stared out the window on the way back from camping).